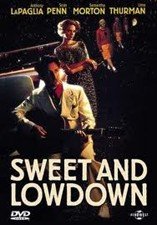

“Sweet and Lowdown” film review, The Daily Cardinal, January 2000

It would be useless to resist placing a new Woody Allen film in the context of his older films. It would also be meaningless. Allen’s films are so personal and so often divorced from current trends that this becomes the only practical context for placing his annual expositions.

So to begin, Sweet and Lowdown, his last effort of the ‘90s, a decade fraught for Allen with rumor, infamy, professional uneasiness and artistic insolvency, is one of the director’s finer outings. Where recent efforts were alternately undermined and abetted by self-consciousness — the arty black-and-white New Wave reverence of Celebrity, his sleazy courtship of the R-rating in Deconstructing Harry and Mighty Aphrodite — Sweet and Lowdown is a return to form epitomized by wistful throwbacks Radio Days and The Purple Rose of Cairo.

While Allen’s allegiance to Fellini persists (notably La Strada), he uncharacteristically evokes Warren Beatty’s Reds by assembling a handful of on-screen commentators, himself included, toward an (apolitical) end: inventing a myth of a mythical character — swing guitarist Emmet Ray (Sean Penn). Ray, in his own mind and in the minds of Allen’s specialists, was second only to Django Reinhardt, a real swing-era guitarist whose influence lingers over the film itself — with supple approximations of his playing style rendered throughout — and the Ray character, who faints in Reinhardt’s presence. Ray grinds along in relative anonymity, condemned to play in Reinhardt’s shadow, apparently, by his incapacity to tap his emotions and translate them in his playing.

Penn’s performance has been somewhat exaggerated in the national press, but is still one of vigor and pathos. Zhao Fei’s elegant cinematography; Santo Loquasto’s discreet production design; the prim delicacy of Samantha Morton’s Hattie, Ray’s mute girlfriend; and the wonderful soundtrack are still more reasons to see this new Woody Allen film. And to see it again.

© 2000

Stephen Andrew Miles